This morning, I saw sedans filled to the brim with pillows and blankets stalled on side streets. Mini-vans poured into campus parking lots. A few stray students toted their suitcases, lanyards already draped around their necks, with their nervous parents trotting behind them. As I weaved my bike through the lines of cars on my way into my office, I heard the thump of a distant stereo punctuated by intermittent welcoming squeals of delight.

That’s right: it’s move-in day for new students here! And while I wasn’t quite sure if I would survive my bike ride through the unusual on-campus traffic, I did not regret bearing witness to one of the school year’s most anticipated rituals: the moment when students get to call campus “home.” I couldn’t help but feel some secondhand enthusiasm and anxiety on their behalf. If you’re eighteen and coming to live at a residential campus, the experience is life-changing. For the next four years, this space becomes both a place of learning and a place of community. At a campus like Stanford, there is little divorcing the personal and the academic, which is what makes college such an existential rollercoaster of an experience. For my undergraduate years, I also went to a four-year school with strong residential life (UCLA has a pretty large “commuter” population, but also enough students living on-campus that the dorm experience felt vibrant and centered), and I can remember the joys and challenges all too well. While I have some nostalgia for college life, I also vividly remember the challenges of co-habitating with different people, of getting sick and longing for the comforts of my own family, and of the sheer stress of making friends and figuring out just where I belonged.

In my current role as an administrator/teacher on a residential campus, I’m struck by how much the place of learning itself matters here and how much the residential experience is emphasized in student pamphlets and among fellow staff. This residential experience, of being face-to-face with other people, is, of course, part of what people come to a university like Stanford for. At a big name school like this, students have been told that a chief advantage of attending Stanford is meeting other Stanford students, becoming part of the Stanford family, and accessing the tremendous Stanford network.

These kinds of factors can make it pretty challenging as an educational technologist to make the case for asynchronous or out-of-class learning. If what everyone comes here to do is to have space together and in-person, why would we even consider incorporating robust online learning into our classes? Why would we want to spend time and energy to conceive of distant spaces for students to connect when students already have the infrastructure to visit each other in their nearby dorms? (Or even have their professors come to them in their dorms for lounge-side conversations?)

I think that even on a residential college campus, students benefit from engaging in online interaction and participating in hybrid learning (that is, partly online learning). Why is that? Well, to me, the answer is actually pretty simple: online learning offers unique affordances to its students that face-to-face learning cannot replicate. Supporting instructors on a college campus like mine, face-to-face learning is valued so highly that if online learning gets mentioned, it often gets assumed to be second-tier or of lesser quality. But anyone who has sat in on a poorly-managed face-to-face classroom experience knows that just because a bunch of people are in a room together, it doesn’t mean that anyone will necessarily want to learn from each other. On the contrary, I’ve had several face-to-face learning experiences where I have felt utterly trapped, unable to get anything of value from the experience, in part because the modality of hearing a lecture or being asked to respond on-demand to challenging questions was not something I could really fully process or appropriately absorb. That is, when I’ve been in unsuccessful face-to-face learning environments as a student, I’ve come to recognize that the environment itself was not all that well-suited for the tasks I had to accomplish. There have been so many moments as a learner where I’ve wished I could just go home and write or go home and let ideas marinate before being asked to act upon them or respond to them in some way.

Time is our most precious resource and if we are not thinking of the ways that we use our teaching time purposefully, taking full advantage of every modality available us, I think we only do a disservice to our work. Knowing what to teach is one thing, but knowing when and how to teach are two other things entirely.

In that spirit, I facilitated a workshop for the instructors I support on how they might bridge face-to-face and out-of-class teaching experiences, working backwards from the kinds of learning activities they facilitate to determine why they facilitate those types of activities and why they choose to facilitate those activities in different kinds of spaces. The results of the conversation were fascinating because they revealed to me that all of us (including myself!) make easy assumptions about what kinds of activities can “only” work in certain spaces. For example, in our conversations, we talked a lot about the value of speaking and movement-based activities in writing studies. Specifically, encouraging our students to get out of their seats, move, and talk to one another we found was highly influential to our students’ learning. And yet, are there ways we could encourage movement offline? What if we asked students to take pictures of different places they’re writing in and reflect on their writing practice? What if we asked students to talk to each other by responding to audio recordings? These experiences obviously cannot exactly replicate what happens in-class, but that’s not the point of the activities. The point of the activities is to think through what we want the outcome of the learning to be and then to choose the appropriate modality thereafter.

I acknowledge that we face important constraints in our teaching through how our classes are scheduled, where they are scheduled, and how many hours per week we are required to work with students. But I also think instructors can and should think creatively about why they make certain choices about particular activities and what the affordances and limitations are to different kinds of learning experiences.

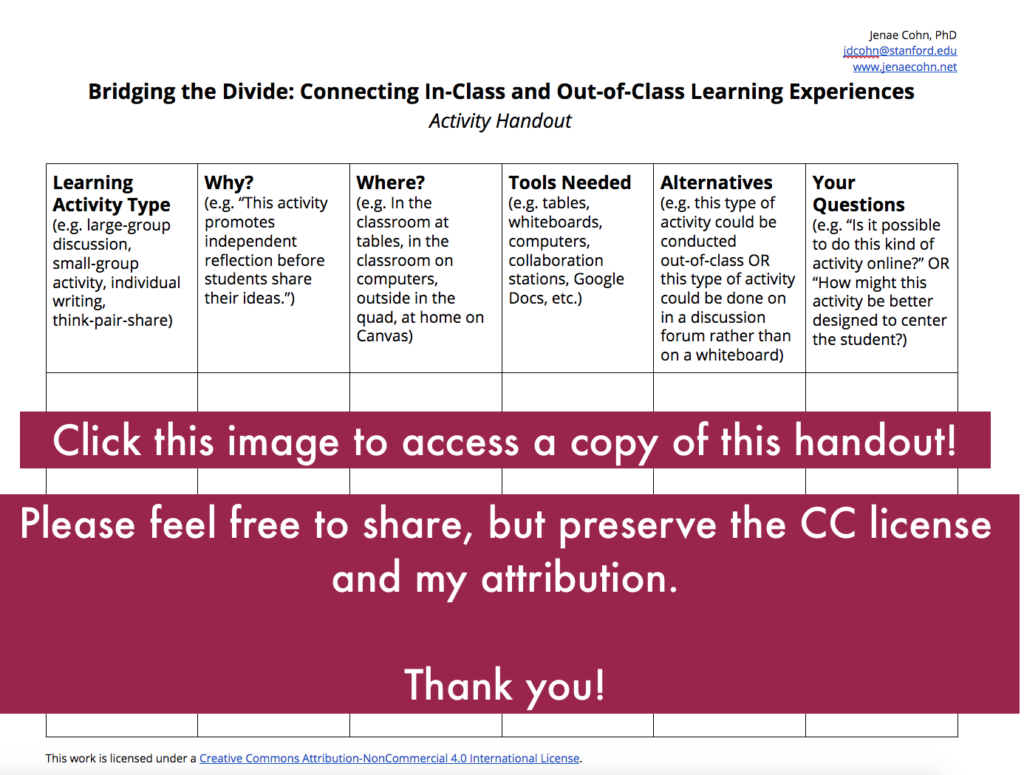

If these thoughts intrigue you, you might find it useful to complete a chart I distributed during my workshop that invites instructors to list the learning activities they do and to consider whether there are, in fact, alternatives to the ways that they currently facilitate those activities. Feel free to check out and make a copy of this handout for your own uses!