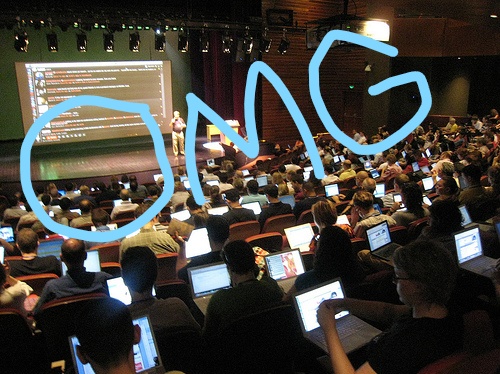

Conversations about laptops in class basically never end. Hence, my, uh, revisions to this image. Originally image courtesy of Alistair Creelman via Creative Commons.

It’s the start of August which, for schools on the semester system, means that instructors are starting to construct their fall syllabi, anticipating the start of yet another academic year. Here at Stanford, we’re on the quarter system, so we’ve got about a month left before we’re in the same boat. But as I’ve been browsing Twitter and LinkedIn, I’ve been seeing images of generated syllabi, accompanying the buzzy (read: anxious) energy of the impending summer’s close (sorry, I’m being a real buzzkill here, aren’t I?).

In light of all of these syllabi cropping up, it seemed timely to talk about a component of syllabus planning that always seems to rile instructors into a heated, ongoing, never-ending debate: technology policies or, more popularly, “laptop bans.”

Technology policies tend to be a statement on a face-to-face (and often, a hybrid) class syllabus about how or whether technology – and this typically refers to laptops, cell phones, and tablets – will be used in class.

This debate seems to incense instructors on both ends of the policy: instructors who ban laptops and cell phones in their classes feel strongly that these technologies distract students and infringe upon their learning experiences. They often point to studies about how students can’t multitask as well as they think they can, how peripheral laptop usage distracts students and lowers student performance, and how students more often use their laptops to check e-mail or go on social networking sites than take notes or research components of the class session.

Just as many insist that laptop bans themselves have significant negative ramifications on student learning. They claim that laptop bans unfairly punish students who may want to use their laptop for their learning, apply a single pedagogical “ban” to a variety of learning situations where laptops may be useful, and can problematically reveal which students have disabilities who must use a laptop in class.

Maryellen Weimer really nails the crux of the problem in her 2015 blog post (yes, we have been treading over this same territory year after year), “How Concerned Should We Be About Cell Phones in Class?“, when she asks, “Are we failing to see that in some ways this isn’t about the devices, but rather about power?”

100% this. Instructors like to ban devices as a way to show that they know better than the students. Sometimes, they do. Instructors have developed expertise in their content areas; that’s why they’re at the front of the classroom. But I don’t think every instructor can necessarily presume to know better than their students about what helps individual students learn. Jesse Stommel has tackled this concern too; much of his writing concerns his ongoing attempts to disrupt the assumptions that can come with a classroom’s hierarchical power dynamics.

I find that every time I teach, I’m always surprised by which lessons stick with which students in certain ways. There is always at least one lesson per quarter that a student remembers and I think, “Really? That one?” The point is, we can’t presume to know what will be best for our students, and much of the scholarship of teaching and learning suggests that we can really, truly help our students learn best when we listen to them, each class, each quarter, and gather feedback along the way to adjust to the various and flexible learning situations in which we will teach.

But recognizing that technology policies of all types are about power is not exactly applicable to our practices. Do we just get rid of writing a technology policy on our syllabus altogether? I’m not sure that’s the answer either; it is important to establish some ground rules and to build a class community with shared values and standards. A lot of instructors opt to write technology policies with their students, a solution that can get at a student-centered classroom. But other instructors may want to set the tone about how technology will be used in their classes, especially if there are particular projects or activities that may centrally involve technology as part of achieving a learning goal. In other words, I don’t know that there is a simple solution here.

I was recently tasked to design a workshop session for new instructors at my institution on crafting a technology policy for the syllabus. I’ve followed the debates on laptop bans closely, and have developed my own strong opinions about the topic, but I knew that just sharing what I thought would not necessarily be persuasive.

So, I came up with an activity that I thought could best capture the complexity of the power dynamics in the classroom: a role play activity, where the new instructors have to embody the personas of the various students in their classes.

I plan to divide the group of new instructors in half. One half of the group will be in a class with a rigid laptop ban. The other half of the group will be in a class with a completely open laptop ban. Each group member will be given a persona to embody in that class. Then, the new instructors will have to talk each other, speaking from the perspective of their student persona, about how they feel about their “teacher’s” laptop policy.

Right now, I have four personas I’ve generated to try and show the range of students and their attitudes towards using technology in the classroom (please feel free to use these for your own training if you want; I’ll probably write these up in a nicer format and re-post/re-edit this when I’ve done so with appropriate Creative Commons licensing):

Student Persona 1:

You are a student who has always enjoyed school, especially lecture-based classes. You’ve always found using a laptop or a cell phone class to be really distracting for you though. If you bring your laptop to a lecture, you know you are compelled to go on Facebook or read the news. You also hate it when your peers are on their laptops or cell phones in class too; you can’t help but glance over at their news feeds when something interesting catches your eye. You really just wish laptops weren’t allowed in the classes; you learn a lot better when you just write out your notes by hand and can pay attention and listen. Sometimes, you’ll use your phone to take a picture of a whiteboard/blackboard, but you’ve read a lot of research showing that taking notes by hand improves your memory and you believe in that strongly.

Student Persona 2:

You are a student who loves learning, but has sometimes found that a traditional classroom environment has not always been right for you. You are a little shy about participating in discussions and tend to zone out during lecture. You’ve learned most of what you’ve really cared about from watching Khan Academy videos and doing the exercises, reading articles on Wikipedia and even editing some entries yourself, and writing up posts on Reddit. In fact, all throughout high school, you always brought your laptop with you and took all of your notes there, often moving between multiple apps to supplement what your teacher is saying at the front of the room or what you hear your peers saying in discussion. When you contributed to discussions, it was a special moment, but you’d often bring in what you learned online. You intend to follow the same pattern at college if you can.

Student Persona 3:

You are a student who is excited to be at Stanford, but who is also very nervous. You are a first-generation college student and you have always excelled in and enjoyed school, but there is a lot going on at home. You know that your little sister is working three jobs to help support your family, while your little brother is struggling with a learning disorder that makes it hard for him to focus at school. Your parents, meanwhile, are also working full days. In high school, you would study really hard and take notes by hand, but you would keep your phone in your lap at all times, texting your sister and brother throughout the day to make sure that they were doing OK. You are also often on Facebook Messenger to keep in touch with your high school boyfriend, who is attending the local college in your hometown and who is also keeping an eye on your siblings. You miss everyone a lot and want to make sure that you can be responsive if something goes wrong, but you are also really motivated to be a focused and determined student, and you won’t let anything get in the way of the opportunity you’re receiving here.

Student Persona 4:

You are a student who has always done really well in school, and you come from a family that is well-resourced and has always supported your education. You feel confident that you’ll succeed in college, but you are often ashamed of the fact that you have a learning disability that requires special accommodations. You have never told anyone about your disability, and while you’ve gone to the Office of Accessible Education and have received an accommodation to share with your instructor, you’re not sure if you want to share your accommodations this quarter because you don’t want your new, tough Stanford professors to think you’re not up for the challenging education you’re about to receive. One of your accommodations requires you to use a laptop, and you were always allowed to use your laptop in high school. You can write notes by hand, but you are much slower at it than on the computer, and being able to enlarge text, find certain keywords on the computer, and record your professor have all proven to be critical to your success.

I’ll be really curious to see how the new instructors I work with negotiate these personas and their potential reactions to their “teacher’s” technology policies. I couldn’t think of a better way, really, to help new instructors empathize with their students and understand that a single policy cannot really capture the range of use cases that students may know about for using their technology to supplement their learning.

If you hadn’t guessed by now, I have almost exclusively adopted an open technology policy, but I also teach discussion-based classes where students use their laptops, cell phones, and other devices for lots of hands-on activities. The opportunities for distraction are often minimized by the pedagogical choices and the assessment strategies that I use. That said, I know distraction is going to happen anyway; everyone gets distracted and attention, to me, is rarely the best metric for measuring student learning anyhow. Not to mention that centering attention as the means of learning is, at its core, an ableist framework that ignores students who manage to learn and excel even if they are not always paying “attention” by remaining quiet and keeping their gaze on the instructor.

So, we keep talking and talking and talking about technology policies and laptop bans because we still can’t really get over the fact that a learning experience is not all about paying attention to the instructor at the end of the day. To assume that we always know what’s best for our students at all times is, to me, an often patronizing perspective that de-centers our students and removes their agency from the experience.

What we can do about is going to depend on the institution, but I think that the more we can bring student empathy and experience back into the situation, the more we can assess and make choices about how we accommodate the diverse minds that will enter our rooms in the fall.

I’d love to know others’ thoughts to this end. How do you talk to your instructors about technology policies? Are there some personas that I’ve missed in my representation that I really should add in to account for a fuller spectrum of student experiences (I’m confident I have)? When do you think we might finally be OK with letting go of power in the classroom?

Amazing and thoughtful post (sharing it!!!). My talk with faculty focuses often on the fact that the technology is a tool and a distraction and it’s often a distraction when the course or format is instruction. I then roll it into a conversation about leveraging those tools to get students more focused on different elements of the class. One way I encourage this is by encouraging faculty to give students an “impossible task”–some kind of challenge that in small groups may be impossible to do (come up with a 10 minute presentation by mid-way in class on subject X to present to others). Here, the technology becomes a pathway to do this and they’re using them as tools (and don’t have time for distractions)–in small groups, they often internally regulate because everyone is needed to get it donne. Afterwards, I the debrief should include a discussiion of the tools used.

In general, I’m like Stommel in that I see the control of the technology as a power issue and represents my own insecurity or frustration that students aren’t engaged about the thing that I’ve studied for years as I am (and that is what students often run up against). I remind faculty that in many of even my favorite classes my notebook was sufficient distraction for me as I I occasional notes in the front but largely wrote and doodled in the back. It’s never about the technology but about the mindset.

Thank you so much, Lance!

I like that you bring up the connections to pedagogy with your faculty. The “impossible task” assignment is really clever too insofar as it makes the technology visible in a way that doesn’t just get mired in ideological assumptions.

And yes, we forget that notebooks are “technologies” too. Something I was tempted to write in this post is that if we banned all “technology” in the class, we’d have to get rid of every writing instrument, projector, and recording device! Thanks again for your thoughts on all of this!

Hey! Really interesting post. I’ve been TAing for a couple of years, so I have typically been observing students from the back of the classroom. I take your point that laptops can be really important for a student’s learning, but I’ve also seen a student trying hard to take notes on paper, but being sucked into the sports game the person in front of them was watching, mid-lecture. As I read, I was trying to figure out if there’s some sort of ‘ classroom geography’ solution. Maybe students that want to not be distracted can congregate on the right side of the room or something like that?

Hi Ryan,

One method that I’ve tried and encouraged with other faculty is to have students who are using their laptops to email their notes to the instructor at the end of the class (or the TA). This creates a level of credibility in that if a student has to produce something (e.g. email the notes), then they feel more need to remain on topic. This also helps the instructor as it tells them how what they are doing is being processed by the students. Also, it gives a chance for a conversation between instructor and student if the student is typing away like the great American novel but merely producing notes that minimum. (This can also be augmented into creating a class Google doc of notes that everyone contributes to).

Thanks, Ryan! I’m so glad that this was an interesting read for you.

I totally feel you on how distracting it can be to see someone watching or doing something that’s engaging or intriguing. I think dividing students into groups can work as a strategy, though we do have to be careful about not “outing” the students who may need to use a laptop for disability purposes (That is, we don’t want to assume that everyone on a laptop is necessarily seeking distraction). But I think the idea here of imagining the room a bit differently and creating spaces for different kinds of engagement is intriguing. What might happen, say, if we asked students to move around the room mid-way through the class session? Or we had one part of the room take notes one way (in a Google Doc, say) and another part of the room create a diagram or an image of what the professor is discussing? I’m really just brainstorming here, but your idea of shuffling “class geography” is interesting here.

I also like Lance’s suggestion about building accountability in the class community too through shared note-taking or turning something into the instructor at the end of class. That might mitigate the sports-watching. 🙂

It seems like both ends of the spectrum (ban the laptops! vs. Laptops are tools to learn!) could benefit from a book I finished a couple of years ago. Have you read Minds Online (Michelle Miller) yet? https://www.amazon.com/Minds-Online-Teaching-Effectively-Technology-ebook/dp/B00O0NP3S2? While the title and some of the thrust of the book is about online teaching & learning, the key word is really “minds.” Her expertise in how learning takes place takes a lot of that polariziation you reference out of the equation, and gives really practical, thoughtful examples of using technology in online learning but also inside the classroom.

What a great book suggestion, Beth! I haven’t read it yet, but it’s been on my list, and it may now even take greater priority for me to read given your comment here! Thanks for sharing!

Amazing and thoughtful post

A key student persona to add to this mix is the student with little interest in the subject, taking the class to meet a requirement. This student has always done well in school by “figuring out what the teacher wants” and “beating the test.” Since social location was important in the profiles, let’s say that this student is comfortably well-off, with no significant care responsibilities or known learning difficulties, and with a big investment in their extracurricular life. And let’s say that this is a Gen Ed class enrolling 90 kids, so maybe 65% of the students fit this profile. And the class meets three times a week for 50 minute periods in a room with fixed stadium seating. I’d appreciate hearing how that student fits into this vision.

This is an excellent suggestion, Trysh! Thank you for suggesting this additional persona. Since I originally wrote this post in 2018, I think there’s a lot more to account for and think about. I’d love to add this to a new version of the activity. Thank you again!

I love looking through a post that will make people think.

Also, thank you for allowing me to comment!