I’ve been at my current job for two years now, and I still find that I’m explaining it a lot to people. The job title itself – “Academic Technology Specialist” – is not particularly clear on the surface and, for anyone outside of a higher education context, it sounds a lot like working in IT and fixing computers. But I have no computer engineering or hardware background, so to say that I could be an IT person is honestly laughable.

So, what is it that I do then?

Here’s the most recent way I explain my job: I support instructors in their use of technology, digital or not, in their classes. In so doing, I help instructors think about their students’ learning spaces and how those spaces might impact how they teach. My central question I (aim) to help instructors consider is: how do we take full advantage of the classroom space you’re using to reach your students and advance your class’s learning goals?

OK, so, that still might not make so much sense to you if you’re not in higher education, so allow me to employ an analogy that might clarify things: instructional designers and technology specialists are like the violas that play in the orchestra. If you don’t know anything about the orchestra (or don’t even know what a viola is), I’ll make this all clear too so that the analogy will continue to make some semblance of sense to you too!

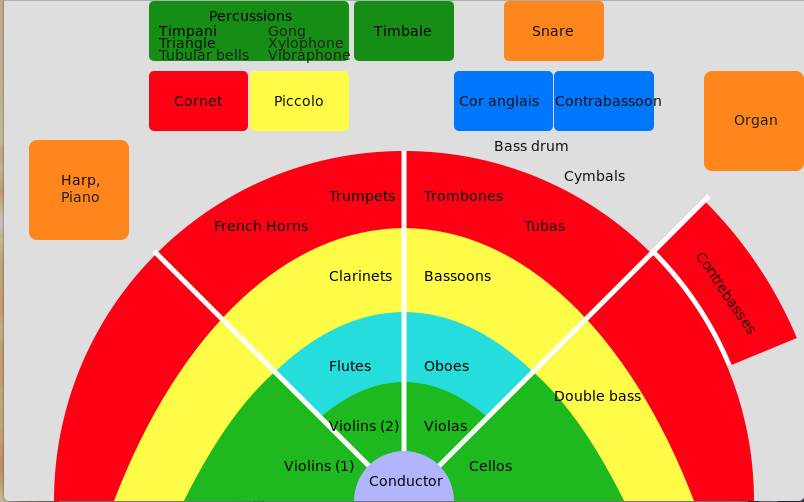

In an orchestra, there are string instruments (e.g. violins, cellos, violas), wind instruments (e.g. flutes, clarinets, oboes), and brass instruments (e.g. tubas, trombones, French horns). Each section of the orchestra plays an important role in the composition of a musical piece, and there are trends in what kinds of roles these instruments play. For example, in the strings section, violins and cellos are better-known instruments than violas because they tend to get more of the flashier solos in symphonic pieces. Technically, this is because violins and cellos have greater musical range (within a single instrument) than other string instruments, but that’s not really the point here. The point is that, instruments are visible in the orchestra in particular kinds of ways, and that becomes even clearer within the clear structure of the orchestral group. The diagram I’ve embedded below is emblematic of that (thanks, Wikimedia Commons): there are clearly designated sections for each instrument, and these sections do not vary at all across regions or orchestras.

The typical layout for an orchestra. This diagram shows the different sections of where instruments sit.

The arrangement of these instruments appears pretty equitable. Violins are, of course, a heavily represented instrumental group (most orchestral scores are written with “first violin” and “second violin” parts; the “first violin” parts tend to do more of the heavy lifting, melodically-speaking). But each instrument still has its clear place and part to, well, create great music!

The viola plays a rather humble role on the strings side in this whole arrangement. They tend to play the harmonies in the orchestral scores. If you’ve ever heard The Blue Danube Waltz (and you have, but if you’re not familiar, the video at the link will trigger your memory; go to minute 2:00 and the melody will start to seem really familiar to you, probably), you’ll hear the violas on the final four notes of the main refrain. I know because I’ve played the viola part on this very waltz. It is… not the most exciting score for a viola; it’s a lot of reinforcing the strict rhythm that a waltz always has to have (you can’t throw those dancers off after all!). But emphasizing the final four beats of the refrain (ba da da dum da – DA DA, DA DA!) is critical to the whole song, well, coming together. Not everyone gets to float through the melody, after all. Someone has to be on back-up.

This is where my comparison to instructional design comes in. Most people attending college don’t really know that instructional designers exist, just as most people don’t really know that violas exist. Students, parents, even several college administrators assume that everything about college courses – from the syllabus to the lectures to the course materials – are all designed solely by a professor. In some cases, that is true. But in other cases, especially in online or other digitally-mediated courses, there is a full team of people supporting the development of the course, from the infrastructure on the course website, to the development of the course videos, down to the curation of the readings and instructional materials. Even classes where faculty make all of the final choices, faculty often consult with instructional designers or learning specialists to make design choices about activities, the balance of in-class work and homework, and the structures of assessments and exams along the way. So, while the instructional designer may often be hidden, a seemingly invisible presence in the classroom, that individual plays a critical role in ensuring that the class runs in a way that facilitates student engagement and, hopefully, learning.

It should, perhaps, come as no surprise that I take great stock in the power of the invisible forces that make something operate. I’m biased, of course. I’m able to make this comparison between instructional designers and violists after all because I used to be a viola player (I suppose I could be one again if I bothered to get my instrument tuned up and repaired!), and now I’m working as a learning designer and technology specialist.

There are times when I wish I could be in the limelight a little bit more, where I could be the one performing and doing the teaching work at the front of the room. There is immediate gratification, after all, in getting to stand out in front of a crowd. Yet there is also a gratification in supporting the full enterprise, in really being the force of a collaborative project. Most creative projects – and I include teaching as a creative project here – are fueled collaboratively anyway, and so working in learning design reinforces the inherent collaboration of the teaching enterprise. That is, by taking on the role of a learning supporter, it is clear that I see collaboration as a central tenet of my identity as a worker. I appreciate that there gets to be a little bit of influence in wherever I go; I don’t just get to have one shining moment, but traces of what I am able to bring are visible in a number of contexts. The viola may not get many solos, but look to any major orchestral score, and you’ll know – you’ll hear – that the viola is there.

This also doesn’t mean that the viola player is not a leader in her own way. Similarly, instructional designers are often leaders in their work. There needs to always be leadership, even among support, to make the work happen. I think it’s often a myth that you’re only a leader if you get seen at the front of the room, but some of the most inspirational leadership can be quiet. I like that quality of the work I do too: that the impacts can be felt even if they’re unseen.

When I played viola in the youth orchestra, a conductor once said that the violas were akin to the peanut butter in a sandwich. I liked that metaphor (and apologies for going three metaphors deep here; I couldn’t help myself). I think I liked it because it reinforced something I knew along: while one might notice the bread in a sandwich first, the peanut butter sandwich is truly nothing without… the peanut butter. I liked to think that was true of the viola: if the viola wasn’t there, you wouldn’t have much left in your orchestra at all.

Similarly, with instructional design, you could still have plenty of faculty who teach their own classes, but what if you added in “the peanut butter” of instructional designers? More connections get formed across the campus community, more influential ideas get shared, and (hopefully) there is more engagement that makes the learning experience sandwich, well, tastier. Or the learning experience feels more harmonious with the “violas” of the instructional designers playing around. Whichever metaphor you prefer here, the point is clear: learning supporters may not get the glory of being the instructor at the front of the room, but they do get the satisfaction in knowing that they got to put all of the learning pieces together. And that sounds pretty good.

Great analogy, Jenae! I love learning about roles that requires humility because they’re typically the most important. I’m curious, since you have a first-hand account of this, do you consider mobile/tablet devices when planning out technology in a classroom more today than let’s say five years ago? I keep hearing from folks around me that have kids in school that the electronics in classrooms today are both critical and distracting. Can you share here (or maybe a link to a blog post) of how you think that’s changing your role?

Hi Mitch!

Thank you so much for reading and for your thoughtful comment here! Yes, I definitely consider the role of smartphones/tablets for student learning much more than I did five years ago, especially since we now know that 95% of college students are bringing smartphones to their college classes (at least according to the latest ECAR report out of EDUCAUSE, which you may find of interest to peruse here: ECAR Study of Undergraduates and Information Technology 2018).

To that end, I think the orientation to seeing a smartphone as a distraction is a pretty limited lens. Mobile devices absolutely can be distractions, but they may also be incredible aids for learning. To me, the key is not to ban these technologies, but, as a designer, to pay additional attention to how these devices could be used to leverage learning and to engage greater numbers of students. I’ve tackled this topic in a couple of posts, actually: “Do Students Need Smartphones for Learning? What Device Debates Continue to (Really) Be About and Why We’re Still Talking about Laptop Bans… and How to Talk about Them on your Campus

Another person whose work you may want to read is Kevin Kelly of SFSU. He has developed a bunch of Lynda courses on teaching with mobile technologies that I think are really helpful: https://www.lynda.com/Kevin-Kelly/4018688-1.html

I would be glad to engage more with this topic! Let me know if you have any follow-up questions!