Protestors band together at the “Keeping Families Together” march and rally at the Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City, UT.

Saturdays have become my “day off” at the institute, and I’m grateful for the distance from heavy brain work on these days. I’ve been lucky enough to get to explore SLC during my weekend time, but today felt particularly special as I had the opportunity to march in protest of keeping families together at the Mexican border.

Walking alongside my friend Christine (who came out to visit this weekend!), my new friends at the NEH institute, and other friendly Utah citizens (I was surprised by the number of warm, spontaneous interactions that happened at the march), I felt the warmth and hope of solidarity. Being at this institute has largely meant being isolated from politics (as I reflected on Day 10), and while having that isolation has been generative creatively, getting out and being around other people concerned about our world and its circumstances felt energizing. Regardless of how invested we are in our intellectual inquiry, we always have to be aware of the human rights concerns happening around us and how those concerns impact the kind of people we support as educators.

The moment most striking to me, however, was when one of my institute colleagues, Rebecca, explained that she wanted to take a lot of pictures at the march in order to show younger people evidence that she tried to fight back against inhumane policy. Her comments resonated with me: having proof that you’ve been somewhere or done something is part of what makes us feel like our actions are meaningful, I think. While not exactly comparable, I immediately thought of the box full of artifacts that I have back at my apartment. Filled with postcards, seashells, flyers, lanyards, ID badges, a full variety of things, this box is my way to remind me of particularly important moments, places, and events I’ve experienced and to provide “proof” my various travels. The stakes of having proof of political activism has a different charge, of course. But I wonder whether the desire to prove materially that we’ve done certain things or that we’ve been certain places is part of the wonder of the print book as an artifact.

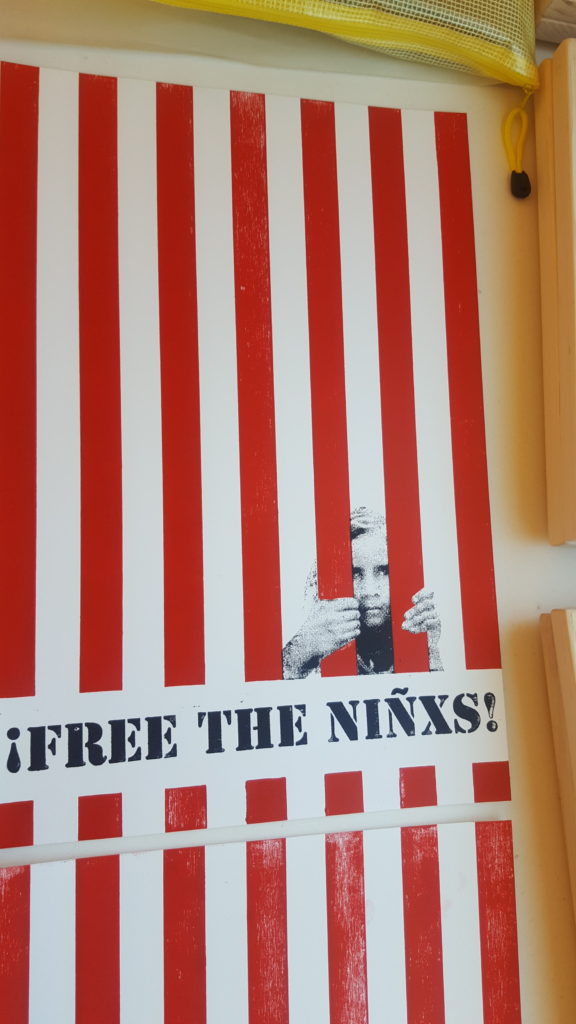

An incredible protest sign, hand-printed and designed by Jamie Mahoney, one of the NEH institute participants.

When I look at my bookshelves, I appreciate that I can remember almost every place I’ve bought the book from (whether it was as mundane as Amazon, as thrilling as Powell’s – the world’s best bookstore – in Portland, or as meaningful as the bookstore at UCLA, where I religiously purchased all of my undergraduate books). Anne Fadiman writes about this feeling extensively in Ex Libris, a book I dived deeply into for my dissertation research and one that I’m constantly reminded of every time I lift a book. Indeed, she compares her memory of her shelves to her memory of her children: she even compares the pages of a book with her children’s skin! That is some powerful attachment right there!

But I think it’s important to recognize that things take on the signification of the place and all of the attached memories to that place (this is in no way an original thought, but one worth acknowledging at this time). I attach this same kind of thingness in a certain sense to my digital devices (it sounds silly, but I have a hard time recycling old electronics precisely because they have played such critical roles in my reading and writing work; my closet is now, embarrassingly, home to two ancient laptops that have long been on the fritz). But part of what a printed book – a codex – does so well is capture one thing in one moment. My computer travels with me virtually everywhere, so my attachment to my computer is more about loyalty than proof of an experience (how could I possibly give up my trusted digital companions when I’ve come to know the shape and feel of their keys so well??). A print book, on the other hand, is proof of one moment crystallized in time. There is a romance to that, the ability to see a thing on your shelf and immediately activate a memory. It makes me think about the neuroscientific implications of a book’s thingness too: is there some part of my brain that lights up and activates memories each time I look at and feel a print book on my shelf? (I’m sure there’s an answer to this).

To return to the political for a moment, I wonder how much “thingness” matters now more than ever. This is not to dismiss the wonder and value of digital things, their easy archivability and, above all, their access. But as we are in a moment where our politicians seem skeptical of history and science, it seems all the more important to me that we grasp on to our material proof of doing particular things, of having something we can hold in our hands and pass on to someone else to say: “This thing was a product of this moment.” To live history, to hold it, to smell it, offers the immediate reminder of where we were and where we have been.

Part of my interest in things right now also comes from another striking moment at the protest: on the steps of the Utah Capitol, hundreds of children’s shoes were lined up in recognition of the children who are still detained at the border. (And I wish I had taken a picture of this; from where I was standing on the capitol steps, it was hard to get a visible shot). I was reminded immediately of an exhibit I saw when I visited Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem, where at the center of one room, a mountain of children’s shoes are stacked behind plexiglass. The shoes made me cry. I did not cry today, but I felt stunned in the same sense: mundane, material objects like shoes evoke tremendously powerful memories and evocations. The shoes, the discarded shoes, of children signify the tremendous loss of basic humanity as they wait behind bars, alone and afraid. It is one thing to see pictures of children at the detainment centers, but it is another thing entirely to see a thing in front of you that offers the reminder that the children detained are not just pictures in a paper, but are people who need shelter, warmth, comfort, and protection.

I wonder if we will always need print books because they will always be that visceral reminder of things that happened or places that existed. Perhaps the greatest affordance to the material object (not limited to the printed book, of course) is the access to memory, to history. And goodness knows, if there’s anything our world needs right now, it is a reminder of the wrongs that have happened in the slightest hope that we may not repeat our mistakes.

Heavy thoughts today, I know (especially for a “day off!” Ha!), but they are thoughts impossible not to have. I’ll end on this image: a child, probably around six-years-old, asks his parents, “Why did the kids get separated from their parents?” His brow furrows, concerned. His mother has no answer. She hands him a sign to hold that read, “Families Belong Together.” I hope this family keep that sign, that material proof that they were there at the Capitol. Perhaps one day, when the child turns into an adult and remembers where he was and how he felt, he might make things different so that his child does not have to ask him the very question he asked his mother.