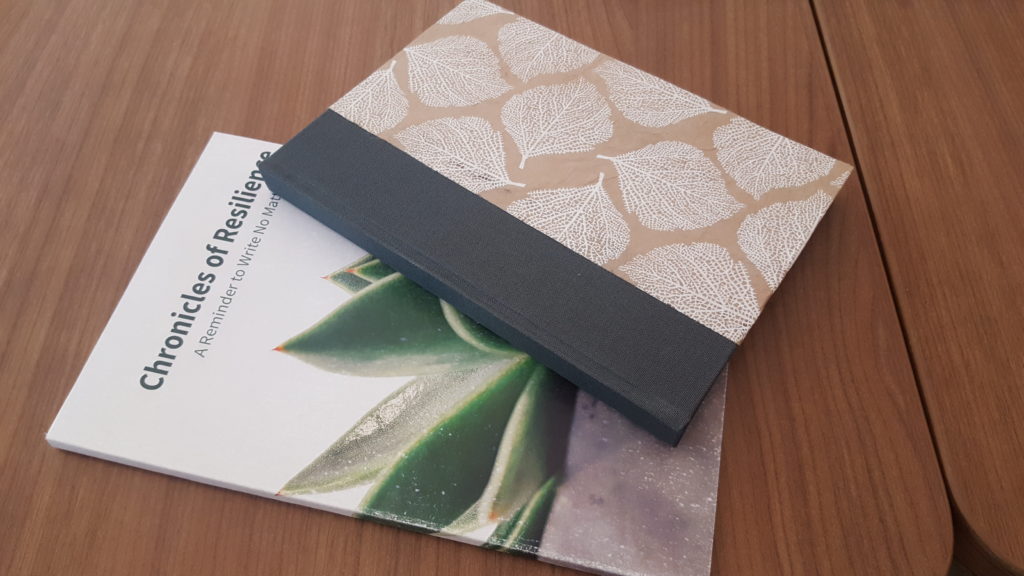

Two books I made this week. The one on the left is a “perfect bind” (the pages are glued to the spine). For the cover, I took a stock photo and positioned it on a page in InDesign. The book on the right is a “case bound” book; the pages are stitched together and the spine and cover are glued to the sewn stacks of pages.

What does it look like to pay attention to someone?

As an instructor, there are few obvious signs that a student is paying attention: they sit up straight in their chairs, they make eye contact with me, and they’ll often nod their heads as they listen in understanding. Verbal cues may also show that someone is paying attention: they might offer an affirmative mumble or, as my friend Mary puts it, a “yummy sound” (e.g. mm-hmm, mmmm).

All of these cues for paying attention suggest a kind of passivity, however. There’s not much engagement when you are paying attention. When you pay attention, all of your energy is driven towards one thing: the person you’re paying attention to.

You can, of course, show evidence that you’re paying attention in active ways. You could ask a question. You could take some notes. You could turn to a partner sitting next to you and whisper a thought or a question to them. Yet the person speaking – the person you’re paying attention to – may not invite these forms of engagement. They might simply want you to listen and expect you to “pay attention” by doing only that: listening.

Learning to be a good listener is critical. We need to listen to other people to hear their stories, to understand their experiences, and to learn from them. The speaker is in a position of tremendous power and control, and in our classrooms in particular, speakers – the instructors – tend to thrive on that power to maintain control over the content being taught. We need to have that control over the space sometimes, but do we need to have control all the time? What is the rule of controlling a space? Why do we need control?

Indeed, I’ve been thinking these same sets of questions in relationship to reading. I’ve come to see that a book, as we know it today, is a way of “listening” to someone else. By remaining enclosed in the pages of a book, you are engaging in the sustained listening to someone else’s voice. If you are a speaker or an author, you are in the position of tremendous privilege, knowing that there is someone out there who is giving you all of their attention simply to hear you out, simply to listen. But, again, the author is in a position of control. By controlling the narrative, the author enacts a certain power over the reader, holding them to attention and driving them through an argument in every linear step of the way. When I read something that I’m trying to dissect, I’m often working to “talk back” to the text, asking questions in the margins or highlighting moments that I think are particularly significant. But this talking back became a sort of developed skill and it remains one that takes me a long time to practice.

More often, I just let the book talk and I listen.

When I read online, I tend to do a lot more “talking” back to my texts if only because I find the experience of reading for entertainment online a lot less pleasurable than reading for entertainment in a hard-bound book. Similarly, I find the experience of reading academic or critical texts online much more pleasurable than reading an academic or critical text in a hard-bound book. So, I find that when there are spaces for me to talk, I talk. And when I simply want to listen, I find that space for listening.

My question today is: how do we, as literacy educators, help students see that we can both talk to and listen to books? That we can be actively engaged, even if the space does not necessarily make it clear that active engagement is possible?

Throughout this institute, my experiences have toggled back and forth between scholarly and engagement and pedagogical engagement. I’ve been trying to understand the lessons I’ve been learning about reading spaces and reading content in ways that will (hopefully) help me do my job better of supporting students in digitally-mediated learning environments, but also that will help me construct an argument for improving our national dialogue about seeing digital infrastructures as a critical part of a reading experience (but not in a way that denotes the “loss” of print or that is hyper-concerned with “diminished ability to learn.”) I think that a lot of scholars tend to see their teaching work as entirely separate from their research, but the biggest reason that I care about this institute – about thinking through listening, talking, and communicating – is so that I can help people have more positive and effective learning experiences, especially when it comes to learning in the humanities.

So, I’ll end today with this question: how do we encourage students to “talk” when they’re often only in the position of listening? And how might we call attention to the materiality of their reading experiences as a way to help them understand what their talking might look like? As always, I am open to your comments and suggestions, as all of these posts suggest entirely work-in-progress thoughts!