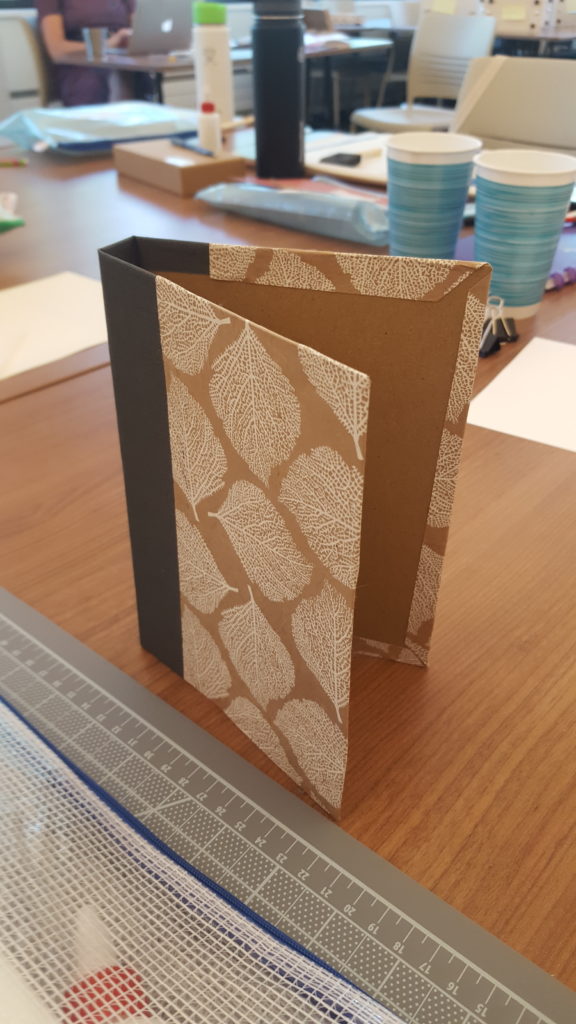

A “case bound” book that I crafted. This is just the front cover, but I actually finished putting the pages inside this book today (I did not give up; a finished product picture TBD). That said, I like the metaphor of a book without pages for considering what kind of content could fill a book, you feel me?

Today’s experiences at the institute made me think about my apartment. In my living room, one whole wall of my apartment is full of bookshelves. They are obscenely large – purchased from a closing Borders bookstore in 2011 – and they fill the room from floor to ceiling. Whenever guests come to my apartment, they are almost all drawn to the living room wall. In fact, I don’t think I’ve seen any friend come into the apartment and not go instantly to the bookshelves to explore what’s there (I’m sorry that I don’t have a picture of this to share because the bookshelves are full of many curios and books).

The wall, the bookshelf, and the books on that shelf are all art of a fairly elaborate performance on my (and my husband’s) part. We are doing rather explicit identity work that we are the kinds of people who own books and who read those books. The fact is, of course, that we don’t regularly read all of the books on our shelves. We swap out a few here and there, but the collection mostly just tends to grow. Kevin, my husband, tends to be much better at pruning back the collection than I am, but I am still compelled to keep the bookshelf full, large, and overblown. I am a reader and this is our shelf and we must keep it full.

Our performance of this bookshelf, of being owners of many books, is a performance largely of our privilege, of our ability to own intellectual capital and to have acquired that capital over many, many years. The fact that we (read: mostly I) have bothered to lug the bookshelves and the books from apartment to apartment suggests that they have value for us, but that value is so largely emotional. Even though we functionally don’t use the books on our shelves very often, their performance serves a critical social function, especially for me, I think, in showing that I am the kind of person who engages in a certain kind of literacy practice.

My awareness of this performance – of its key social function in identifying myself as a “reader” – does not necessarily change my behavior, but it does make me wonder whether there is something about my performance that reinforces the hegemony of particular acceptable reading behaviors. Indeed, if I’m going to read the kind of hardback or paperback book on my shelf, it will typically be literature. My functional books – the ones I use for research and teaching – are almost entirely digitized. There are few visual traces of my work (but for a few textbooks I bought in graduate school), so the space becomes a kind of ode to my leisure time. To what extent is maintaining this curated bookshelf a symbol of my own classed, leisure status? To what extent am I erasing or ignoring the very important ways that I engage in digital spaces? There is one simple way to answer this question, of course: there isn’t a great way to “display” the digital literacy work that i do (unless I decided to install some kind of elaborate digital installation, but that seems like a bit “extra,” as my Gen Z students would say). So, how might we, in our everyday lives, make the acts of engaging in and choosing digital reading practices more visible?

Maybe my living room design does not need to be re-done, but I think that the symbols educators use to represent reading, writing, and communicating could go beyond the visual iconography of the printed, paperback or hardback book. Specifically, the visual iconography of the book is tied to a very narrow range of practices that tend to erase the kinds of complicated engagements that should ideally happen for and across communicators. That is, reading a paperback book can often become a very passive exercise, when reading itself should be something far more active, dialogic, and conversational.

Our institute’s guest scholar today, Johanna Drucker of UCLA (go Bruins!), made a powerful claim that I want to be sure to highlight here:

“A book is a space of commentary and community formation. Whatever its technological production, it lives within communities of practice. How does a book get structured to serve communities?”

I think these statements and questions are critical to understanding what the role of “a book” might be in a digital communicative era. How might “a book,” whatever form that takes, serve the needs of readers? Of writers? What is the object function of a book in a moment when, historically, we have choices between reading on print and online?

I still don’t have answers (it’s only Day 4, people!), but these are the kinds of things on my mind today.