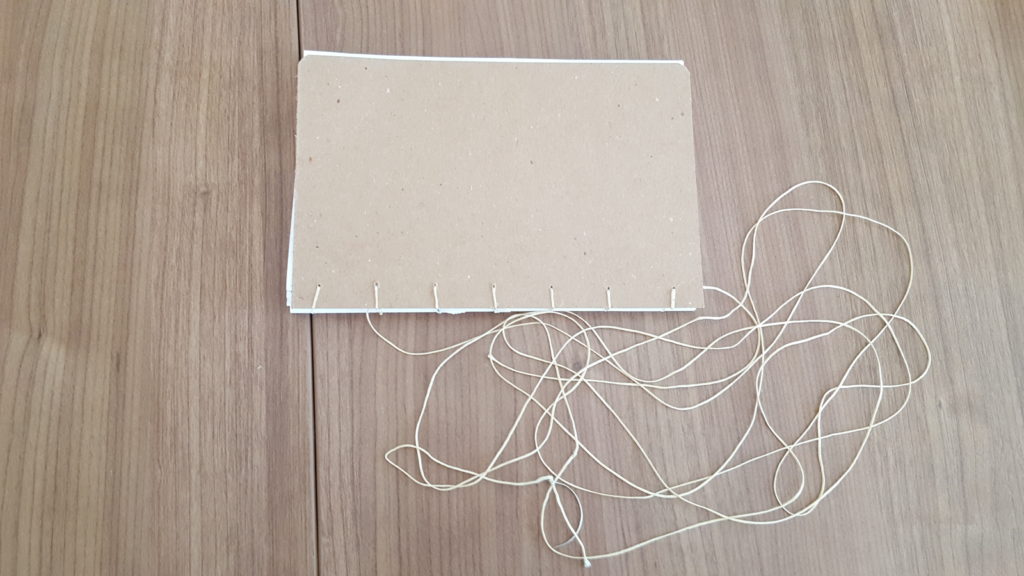

My incomplete (and kind of failed) coptic stitch book. I ripped some of the paper while sewing.

Yesterday, I sat at the desk, hunched over a piece of wax thread, and a stack of papers. I was supposed to be making a coptic book, a medieval style of book where the papers are woven together to create an organically coiled binding. The process is strenuous, time-consuming, and intricate; there is a set pattern for creating the binding to hold the pages together in a complete way and, if that pattern is broken, the book falls apart. As I weave, loop, and strand the pages together, I feel my anger grow. Why am I doing this? What’s the point of creating this coptic stitch book? Why am I spending my time on an obscure, outdated craft when I could be writing? When I could be communicating with my colleagues? When I could be designing a class? When I could be doing literally anything else?

It struck me that this frustration was not an isolated episode. In fact, it reminded me precisely of how I felt when I took an online coding class. There were clear rules and patterns that I had to follow to ensure that my code would operate, that the computer could understand the calculation I made. One misplaced comma, one missing bracket, and the whole thing would fall apart. Just as the pages of my coptic stitch book were loose and raggedy, so too had I seen computer code fall victim to my own loose and raggedy practice.

What was clear to me was that the act of generation itself – of creating an infrastructure to hold and communicate information – required a kind of patience and precision that I struggled to practice. Beyond that, this work of creating infrastructure, or a space to hold information, whether that was a book I created from scratch or a code I created from hand, required a different kind of literacy than the one I had been trained to practice for my entire life. Indeed, my education throughout college and graduate school mostly rendered the infrastructures I used, the tools that I worked with, and the spaces that I thought in, invisible. But here I was, building these things from scratch, and the labor that went into these things was suddenly brought into sharp focus. As an educator, it made me wonder: should we all aspire to create infrastructure from scratch? Or if we don’t have this aspiration, should we understand why building things matters? What we learn from the process of building?

I wound up processing this thought with one of the other institute participants on our shuttle bus today. She made the point – an oft-cited one in the works on multimodal and multimedia communication – that the form of any piece of writing should impact the content. Indeed, the form I’m writing in now, this blog post, very much impacts the choices I’m making in the length of my paragraphs, the presence of images, and ideally a few hyperlinks (though I’m being somewhat lazy about that at the moment).

So, it makes sense, in many ways, to take on a project of “building” as it makes room for a different kind of writing to happen. Indeed, someone writing in something like a coptic stitch book may wind up writing a creative piece that appears very “organic;” one of the institute’s co-organizers, in fact, used her coptic stitch notebook as a travel journal. Indeed, the coptic stitch notebook, a labor of true love and patience, seems like just the kind of place that one might inscribe one’s intimate memories of a travel experience. She may not necessarily have found that a typed page would have been the best form to preserve her memories of the trip, especially since she even used the coptic notebook to preserve organic matter, like pressed flowers, travel brochures, and event tickets.

But for me, I’m still trying to understand what I get out of building in and of itself or how this process informs the project I want to take on in exploring the ways in which literacy crisis emerges from moments of major technological change.

I’m still not quite sure I have an answer yet, but what I’ve come to accept today is that I’m not going to finish my coptic stitch book. And I’m OK with it.

Why? Because I got what I needed from the activity: an awareness of a new form and what it might offer me as a writer and even a reader. Finishing it was not going to help me accomplish anything more from the activity. There may have been something satisfying about having completed it, but what I’m more drawn to right now is turning back to the projects that I really have left incomplete: the intellectual inquiry I want to engage in and the exploration of the forms that I want to use to express my ideas. I am certain that the kinds of things I want to write about would not make sense to communicate in the form of something like a coptic stitch notebook. So, I’m not going to do it. It’s as simple as that.

I wondered whether my “quitting” was a kind of cheating at this activity or a way for me to skirt my way out of something deeply uncomfortable. (As some readers of this blog may know, I have never considered myself much of a crafter and, indeed, I often joke that I have a “craft phobia,” developed over years of having my arts and crafts corrected by adults and experts). Am I resisting learning and growth in favor of reinforcing skills I already have and developing strengths that I have already spent years cultivating? Maybe. But I’m also aware that I only have so much time and my time to answer the questions that have been reeling through my head is limited. There will come a moment when the project of exploring the moment we’re in – a moment of technological change and of hybrid digital and print communication – will no longer be a moment. So, I have to seize it while I’m here.

To me, that’s not giving up. That’s accepting the incomplete, and moving my way into something perhaps even messier and more incomplete than the abandoned coptic stitch notebook.