As a child, I had a recurring bodysnatching nightmare. In the nightmare, I would be safely tucked into my bed, but I would then sense a glowing presence moving down the hallway that separated the front door to the house from my bedroom door. I would stay frozen under the sheets of my bed, pulling the blanket up slightly so that it covered my ears, but my gaze would remain on the hallway as the presence drew closer and closer. The presence would eventually approach the frame of my bedroom door and its full form would become clear: it was a humanoid creature, but with tentacles for legs and arms that were merely wisps of cloudy air. Its face had only eyes and a mouth but no noise. While its outline glowed, its body was the color of smoke and its presence just as seemingly ephemeral. While I pretended to be asleep, the presence entered my bedroom and eventually hovered over my body and, somehow, I knew that it deigned to inhabit my physical presence so that it could snatch a body and take on a solid physical presence of its own. Just as the presence was about to attempt invasion, I would wake up, startled. I would often double-check to make sure my bedroom door was actually closed (my real life self thought that if the door was shut, the nightmare presence couldn’t possibly make its way into my bedroom).

My particular body snatching nightmare eventually faded from my nightly rotation, but the deep, ingrained fear that my identity could somehow be taken away from me, that my body could somehow be filled with someone else’s thoughts or that my thoughts could somehow be put into a different body continued to disturb me. The notion of body snatching has long been a popular fear in the American imagination too. How many stories of embodied possession and zombie takeovers have we encountered in the Western world? (A lot, and many other people have theorized these stories better than I. See, Jesse Stommel on “The Dead Things We Already Are,” Joe Fassler on Zombies, and Sarah Juliet Lauro on More Zombies).

The idea that anyone could willingly take over my body without permission was a fear, I see now, of losing agency and not having the ability to determine when I could use my own voice and how (this is not an uncommon fear or one unique to me). I realized when I was young that my voice was essentially all that I had; my body was certainly a vehicle for that voice, but it only mattered insofar as it was attached to the voice. Once that voice was gone, well, the body was merely a shell.

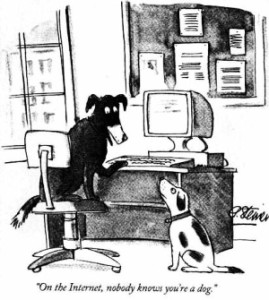

I’ve been thinking a lot about body snatchers as I’ve been thinking about the Internet and the crisis we’re facing at this moment in the early twenty-first century about credibility online and how people distinguish and understand information. I’m realizing that it’s a “body-snatchers” problem too. Online infrastructures take various forms and disguises, but without knowing who’s writing on the other end, anyone can take any amorphous form to represent any idea from any voice that they so choose. As a popular cartoon from The New Yorker concludes: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

The joke of The New Yorker cartoon is predicated on “body-snatching” anxiety: that if any dog can write online as an authority, the fact that you are a dog doesn’t matter in building your potential online persona. That said, this “body-snatching” anxiety is nothing new; we can trace back the anxiety with “body-snatching” all the way to the disembodiment of spoken voice from physical body with the simple act of putting pen to paper. That is, the rise of print culture – and the subsequent technological revolution of mass printing and mass literacy – made it very easy for someone’s words to become something far, far removed from their own bodies. “When you write a book, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

To overcome the anxiety that dogs could be writing printed books, we developed a really strong connection between printed literacy and the educational system. Basically, around the same moment that books, newspapers, and printed materials were distributed in the Western printing world, so too were children being sent to school, not as laborers but as learners. Mandatory public education became a hallmark of the Western world at roughly the same moment that print literacy as social practice became ubiquitous for anyone of any social class. Print literacy was made authoritative in the classroom: teachers passed down the proper books for their students to read so that students could learn (mostly) about how to become good Christians. While plenty of adults received their access to writing through newspapers and paperback novels, the authority for those sources proved exceedingly questionable. These sources were sinful, sensationalistic, and not vetted with the authority of God. In other words, when there wasn’t a body present to assure individuals that the source was trustworthy, we used another body transplant of authority, like a teacher or priest, to help us understand what was OK and what wasn’t.

The main difference between the era of mass print literacy and conceptions of authority then and the era of mass digital literacy and the conceptions of authority now are that we have started to lose trust in our authorities and are not sure who to turn to in order to reclaim that trust (David Roberts’ piece in Vox on America’s epistemological crisis is tied not only to the authorities behind news media, but authorities behind any research-based institution, in my opinion). News outlets and “mainstream media” sources are no longer authorities, are no longer trusted bodies that can communicate disembodied voices. Even schools and universities are no longer perceived as fully authoritative or expert spaces. So, what do we do? What happens when material and infrastructural frameworks slip away and we fear that all of the expert bodies have been snatched by inept ones?

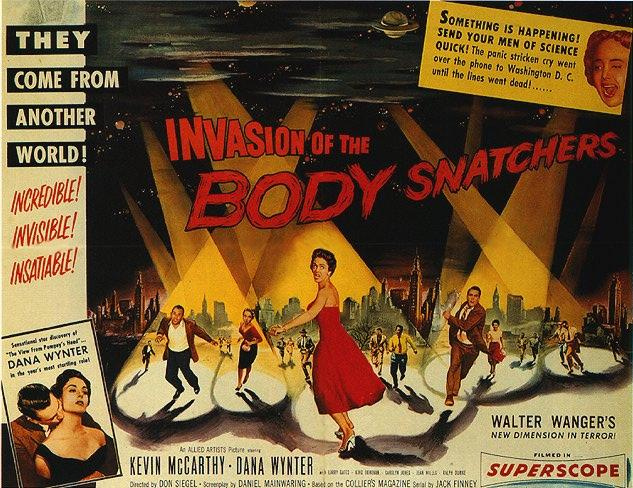

In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the body-snatching threat only stops when police authorities finally see the evidence of the seed pods that are invading human bodies. In zombie lore, the zombie virus only gets destroyed when the zombie body is killed; the human body cannot be restored once the zombie virus has taken over. So, if we’re looking to fiction for our answer to this question, it seems like there’s only one option: annihilation.

When it comes to real world body-snatching, however, I don’t think annihilation of threatening information sources is necessarily the right answer, mostly because it’s impossible. If we are to maintain a free and open flow of information, we have to give everyone an opportunity to share and circulate ideas, even if those ideas are treacherous and tricky. So, one way we can annihilate anxieties over “body-snatching” is by disambiguating who or what is snatching our bodies from the start, making transparent the processes and practices that go into making information, whether that information comes from a book or from the Web. In other words, we need to distinguish between the appearances of alien seed pods and the appearances of – well – humans to regain trust in our bodies again. In non-metaphorical terms, we need to distinguish between trickster writers and trusted writers, and understand what these trusted writers do to find factual information and, well, why that matters.

There are a lot of resources to help readers understand what fact-driven, research-based writing is and how people do it, so I won’t rehash what others have described in better and clearer terms than me. Instead, here is my annotated list of resources I think are really useful about this topic in the hopes that you may explore them further and overcome your own fears of body-snatching and related anxieties:

- Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers: Michael A. Caulfield

- “Fact-Checking at the New Yorker:” Peter Canby

- Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication

So, why might it matter to see concerns with source credibility through the lens of body-snatching? Well, I think it helps us understand the extent to which fear and mistrust guide our decision-making. If we think that information is coming from people or sources we trust, we are more likely to follow them. When we discover that the sources we trust are not who we thought, we feel misguided, concerned, confused, and de-centered. It’s not that we can’t trust anyone, but if we are able to look for the signs that allow us to frame sources effectively, we can understand whether the bodies have been snatched already or not.

I still fear body-snatching insofar as now that I have a much more established voice in a larger online conversation, I know that my identity could be easily stolen or threatened. That said, I know that body-snatching is part of the risk of entering into public discourse without my body to advocate for me. It’s the risk we all take, all of us who dare to put ourselves online and out into the world. We have to trust that readers will come to understand who and what body snatchers do and how to distinguish the real voices from the fake ones.

Today, I try to stay brave enough to keep my (metaphorical) bedroom door open and trust that I will wake up in time to blow the body-snatching smoke monster away. As an educator, I hope to give my students that same strength too, and the critical ability to understand when body-snatching is real – and when it is truly a figment of a nightmare.